Untitled

The Tetley, Leeds

24 Sept 2019 → 19 Jan 2020

When I was a student, I made a video in which I ran naked around the perimeter of a closed room of Victorian paintings in Leeds Art Gallery. The camera was mounted on a turntable in the centre of the room, and it recorded a hundred laps before I collapsed. The footage was then looped so the running never stopped, making me appear doomed to continue the humiliating, nightmarish performance interminably. The video addressed the anxieties I felt about public exposure and how to develop a relationship to the histories and institutions that artists are supposed to situate themselves within. I was terrified of being trapped in a perpetual state of in-betweenness.

Untitled revisited the video’s themes twenty years later, but through the form of an exhibition rather than an artwork. Exhibitions generally allow for a more stratified approach to making, and for the possibility to consider a variety of situations in which such anxieties and fears can be addressed. Solo shows can exert similar pressures, as they aim to present a unique vision that has been honed and perfected through practice, that connects an artist’s inner world to the world at large.

Untitled was an attempt to generate a space of uncertainty between a group exhibition and a solo show. It contained drawings based on, or directly representing, the work of other artists, a strategy that perhaps made it appear at times like a “fantasy exhibition” of objects that I could never hope to gather together at the same time. Alongside these drawings were works by contemporary artists who have influenced my thinking, whether they are peers with established practices, or younger artists with whom I have worked in my role as a teacher. It also contained historical works and archival material that I encountered whilst researching the exhibition, some by well-known artists and some by artists who sit outside dominant historical canons. In its totality, Untitled was an attempt to unpack how subjectivity and artistic identity is produced, and to represent creative practice as a set of personal, political and institutional entanglements.

The exhibition took place across the entire first floor of The Tetley, Leeds in eleven distinct spaces. The architecture of the building is such that in visiting each space in order, one travelled in a full circle, arriving naturally back at one’s starting point after encountering the final space. It was organised such that that a visitor could start at any point along the way, and then follow the exhibition in order from thereon, rather than having a distinct ‘beginning’ and ‘end’.

The works in the show could be meaningfully clustered in many different ways, through their content, form, methodology or medium. There are themes and ideas that are peppered throughout the final exhibition form, such as amateurism, appropriation, influence and authorship; which could in turn be unpacked through a lens of – for example – power, colonialism, identity or orientation. For ease of navigation, however, the exhibtion was organised into overlapping clusters as follows. Please click on individual works or artists for an expanded description:

Atrium and Galleries One, Two & Three

This section of the show contained work that attempted to pull out narratives that have generally been obscured by more dominant, related narratives. The starting points for the works in the Atrium space were the creative and scientific outputs of two nineteenth-century women whose work had been halted or obscured as a result of their becoming committed to the endeavours of their famous husbands. By rethinking their work as sets of instructions for encountering the world (in opposition to their husbands’ modes of address, which are to explain how the world is), it became possible to devise a more open and generative way of making and seeing. In Gallery One was the work of Joan Moore, whose work emerged out of a set of essential, lived experiences of making. Her ouvre runs counter to the dominant forms of late-modernism, and the only public displays of her work from her lifetime were generally mediated through the paternalistic and patronising writings of her famous artist husband’s circle of friends. She chose to live separate from him, hundreds of miles away, and was never given an institutional show of her own. Her work was shown alongside that of John Atkinson Grimshaw and Scott Rogers (Galleries One and Two). Grimshaw is famous for his dazzling technique, despite being a self-taught artist. In this show I read it as evidence of cultural anxiety and a fraught relationship with the institution of art. Rogers’ work also dealt with technique, and notions of insider/outsider-ness. For example, his replica decoy references the use of such objects as – during the colonial era – a means to trick birds into believing it was one of them, and – in the contemporary world – as a form of cultural asset. In Gallery Three, my own drawings of Pukamani refered to a particular transaction that was made between an Australian museum and the Tiwi community. They sought to unpack the tensions inherent within discussions around who defines and decides what cultural production is, and what happens to the objects of such production as they move between oppositional spaces.

Read more about:

Galleries Four & Five

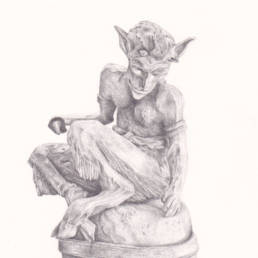

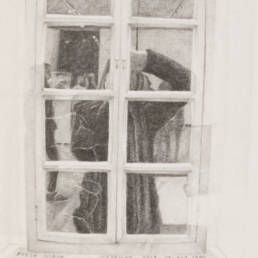

This section overlapped with the previous section in its unpacking of ideas around museology, appropriation, replication and ownership. Gallery Four contained a replica of an ancient sculpture that was ‘relocated’ from northern Italy to England and then split between Leeds and London, an object that offers the possibility for the unpacking of ideas around colonialism, but also museology in general. This was shown alongside two drawings of a Gauguin sculpture which, despite having never actually existed in the first place, became the subject of unusual case of forgery in the early 2000s. In Gallery Five there were two ‘diptychs’. One showed two almost identical images that were, in fact, produced by two different artists: Albrecht Dürer and Marcantonio Raimondi. These two prints represented an early legal battle over copyright infringement, in which Raimondi had copied a Dürer print that he bought in a Venetian market and passed it off as his own work. On the opposite wall were two drawings of Morandi paintings made from photographs that should have been destroyed. The image of each painting was obscured by the addition of marks made by Morandi in order to destroy his printing plates once an edition had been completed.

Read more about:

Galleries Six & Seven

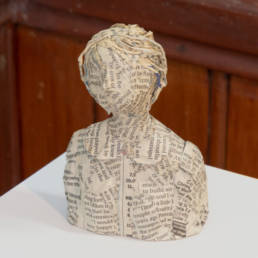

The next section of the show continued to carry themes addressed earlier in the show, but began to deal with ideas around materiality, and how it is infused by the psychological state of the maker. Overlapping with the previous section was a set of images of paintings owned by the collector Guglielmo Achille Cavellini. Cavellini attempted to transition to being an artist rather than a collector, and did so by using objects by other artists in his collection as material. This, inevitably, had a catastrophic effect on his relationship with the insitution of art. Also in Gallery Six was a video by Sarah Forrest in which she recorded the production of an object that she needed to make in order to retain a tactile relationship with the world. She constructed an elaborate fictional scenario and methodological approach to making in order to satisfy her craving without compromising her public persona / artistic identity. This was shown alongside a set of paper mâché busts made by my mother while she was receiving chemotherapy, utilising pages from newspapers reporting on Edward Snowden’s activities that I had collected in Hong Kong. This work attempted to utilise very simple materials and images to collapse complex personal and political narratives into one another. The last work in this section, which appeared in Gallery Seven, was a watercolour by Richard Dadd of a market scene he encountered while he was accompanying an aristocrat on his Grand Tour. Dadd had a extreme psychological collapse on his return to England, and painted images of the tour whilst being locked up in Bethlam asylum. The painting is completely unrepresentative of Dadd’s mental state, and as a result seems to me to recall Frantz Fanon’s assimilation of mental-illness and the colonial gaze.

Read more about:

Galleries Eight and Nine, & The Shirley Cooper Gallery

The remaining cluster was constructed around ideas of education and learning. Helen McCrorie’s video in Gallery Eight showed pre-school age children exploring a former military facility that has now been partially reclaimed by nature, and is being repurposed for – amongst other things – electronic data gathering. In Gallery Nine was a set of drawings I made of Duchamp’s Readymades copied from images posted online as they are encountered in museums and galleries around the world. My own drawings were replaced over the course of the exhibition by copies of the same images by three young artists – Jess Carnegie, Marguerite Carson and Noel Griffin – who I supervised as they wrote their undergraduate dissertations. Many of the ideas discussed in the wider show were discussed with them individually whilst we were all working together. Finally, in the Shirley Cooper Gallery were artworks, videos and ephemera relating to Harry Thubron, the pioneering educator who transformed art education, initially in Leeds and initially in the wider UK, through the innovative teaching work he did in the wake of the Coldstream Report. On exiting this section, visitors would find themselves back in the Atrium.

Read more about: