The Landis Museum

Chapter Thirteen, Glasgow

20 Apr 2018 → 7 May 2018

CCA Derry-Londonderry

26 May 2018 → 28 July 2018

For over twenty years, Mark Landis spent his days making copies of pictures he found in auction house journals. When he was happy with the results he would get in touch with various museums, primarily in the southern states of the USA, to arrange a meeting. On his arrival, he adopted an alter-ego – most commonly a Jesuit Priest called Father Scott – and attempted to donate his work to the museum’s collection, claiming that the object was part of his mother’s estate. It is not clear how often his gifts were accepted, and – on the occasions they were – how long each museum took to recognise the object as inauthentic. In 2010, following a failed attempt to gift a painting to Hillard University Art Museum in Lafayette, a number of articles were published in national newspapers that exposed Landis’ activities. Since the pictures he was gifting were copies, and since he pretended they were authored by well-known artists, it seemed like a straightforward case of forgery, and this was the story that was spun.

The objects were often described as being ‘masterful’ or ‘brilliant,’ but it should be immediately clear to any reasonably experienced curator or registrar that there are problems with the works’ claims to authenticity, no matter what supporting evidence Landis supplied. They are generally made with the ‘wrong’ materials, such as acrylic paint or marker pen, and with embellishments that ‘compensate’ for seemingly poor reproductions in catalogues, such as making a dark sky bluer. As a result, when one sees Landis’ objects for the first time, especially in full knowledge of the dominant narrative surrounding him, it is not uncommon to feel a sense of disappointment that they aren’t ‘better.’

The starting point for this exhibition was a reinterpretation of Landis’ objects. Rather than viewing them as forgeries, they were instead seen as props that enabled Landis to generate a kind of short-lived social hit, which developed into a full-blown addiction. He wanted to be a philanthropist, but had neither the financial nor social means, so he made his objects in order to facilitate an encounter that enabled him to play at philanthropy. When Landis sat in a curator’s office, he could not, for obvious reasons, claim any authorship of the object itself, nor of the mechanisms that brought it into his possession. If the object is a hopeless forgery, then that’s the fault of either his mother or the auction house that sold it to her, rather than his. So in that sense, it didn’t matter whether the curator believed the work was genuine or not, as long as the meeting was enacted cordially and professionally; and it also didn’t matter whether the object was accepted, directly declined, or even disposed of after he left. It was at the point of the encounter, which took place at the institutional border, and in which the structures of patronage exploded into view, that the work was truly operational.

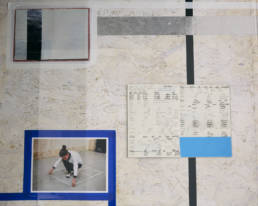

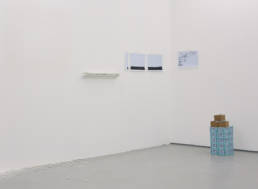

The Landis Museum was a site that pointed to other such moments, which brought works by multiple artists together in the spirit of the encounter. The works contained within it were not about Mark Landis, nor any other wider social, political or aesthetic concerns connected to him. Rather, they existed in their own social, political and aesthetic realms, and were there as a result of their relationship to the encounter in its widest possible sense. They were arranged on and around a single display object, bringing them into physical and aesthetic contact with each other.

Sarah Pierce

Lost Illusions / Illusions Perdues, 2014 / 2018

Performance, two-screen installation (17 mins), photographic documentation, dismantled plinths, glass.

Sarah Pierce’s work for The Landis Museum was a coupling of disparate exhibitionary moments that coalesced around two equally disparate narratives. For her 2014 exhibition, Lost Illusions/Illusions Perdues, she developed a series of exercises for graduate students based on Brecht’s lehrstücke or learning plays, which were performed at Mercer Union in Toronto. These exercises, gestures and chants were recorded to video and displayed on two screens along with props from past exhibitions. In The Landis Museum, the work was shown at the entrance, to set the scene for the exhibition, the screens sitting on the dismantled support structures from a previous installation of Mark Landis’ work in Glasgow in 2011. Pierce contextualised Landis in relation to Honoré de Balzac’s character, Lucien Chardon, who struggled to read and replicate the mannerisms of 19th century cosmopolitan Paris. The on-screen performance was reenacted in the Glasgow iteration of The Landis Museum, thereby existing in duplicate, as a collective, repetitive struggle with translation and form.

Irina Gheorghe

Foreign Language for Beginners, 2015 – 2018

Performance, notebooks, screen print, photographic documentation, tape

Irina Gheorghe showed her evolving performance work, Foreign Language for Beginners, during the opening weekends of both the Glasgow and Derry/Londonderry versions of the exhibition. On the exhibition structure, her performance was represented by the notes, documents and a screenprint from its ongoing development. Foreign Language for Beginners looks to the future to address slippages in gestural and linguistic communication, speculating on how we might ‘speak’ to aliens at a point of first contact. How do you build a language if you don’t know what it will be used for? How do you deal with a reality you can’t access through experience?

Alexandra Sukhareva

Trap, 2015

Fibreglass

Bracket (Bayham Abbey, Mykenae and Sirmione), 2013

Photographic documentation

Seemingly inaccessible forces were also present in Alexandra Sukhareva’s work. Her objects, which represent central points of contact between herself and either identified or unidentified others, often exist in physically or psychologically precarious states. In The Landis Museum visitors encountered two tubular objects which were made as a means to cure her sick friend, without his knowledge. They were intended to act as a trap for his disease, to draw it in and contain it, but also to offer her solace during this time. When he unexpectedly recovered, she came to see these objects in relation to the so-called Zagorsky Experiment, in which deafblind children were taken to the studio of the artist Vadim Sidur, where they experienced his sculptures through touch, an example of a set of active communal encounters that were experienced internally and psychically. She views her objects, at the point they become shown as ‘art’, to be in a state of exhaustion.

In another intermediary action, she inserted ‘brackets’ into the architecture of important historical sites in Italy, Greece and England. Appearing to be handles of some sort, they would be grasped at by visitors but would come away in their hands, creating a temporary moment of alarm, alerting them to a sort of third space between the past and the present.

Alex Impey

Flower, 2018

Milled HDPE, 3M respirator seal

Flower, 2018

Plastic, sea urchin spine

Flower, 2018

Everted car ducts, wire, sleeve

Alex Impey’s objects also operate at mid-points, or as ‘hinges’ between different points in a chronology of knowledge. He considers the ‘terminal form’ of art objects as a kind of clogging, warning that they should not be thought of as summaries of what has already happened in the pre-production or research phase. The materials also seem to function as mid-points, this time between natural functionality and a synthetic or industrial functionality, and it is this ambiguity that determines their often-strange final form.

Bianca Baldi

Insufflate, 2016

Dalmatian jasper, copper, tenth paper

Snake Weight, 2016

Dalmatian jasper, fabric

Bianca Baldi’s, Snake Weight, took the shape of an object commonly encountered at sites of research and knowledge production, such as archives and libraries. Such weights are generally used to hold pages flat, but Baldi’s object carried a ‘double heaviness’, as the jasper stones providing the weight could be joined in a similar way to make a similar form: that of a talisman, which provides protection against unknown forces and grounds its wearer in the sensible world. The snake was, simultaneously, an intermediary object and one thrust into the foreground – it was both a prop and a presence.

Also present was Baldi’s work, Insufflate, in which the jasper appears once again. This time it held a piece of tengu paper in place on a copper printing plate. Tengu paper is the lightest paper in the world, so light that it resists printing and is easily blown in even the gentlest of air currents. Here, Baldi further problematised processes of knowledge production, this time publishing, which can be both a form of resistance and enlightenment, but also a key tool in the entrenchment of existing power-relations through the embedding of dominant narratives.

Kapwani Kiwanga

Brass Healing Bowl, 2016

Hammered brass concave bowl

Man Pulling at his Beard, 2016

Terracotta Brick

Cape, 2016

Felt, cotton, beads

Transfiguration Tripod, 2016

Ceramic

The Secretary's Suite, 2016

Video, 23 mins

A further form of doubling could be found in Kapwani Kiwanga’s objects. Working with staff at Berlin’s Dahlem ethnographic museum, Kiwanga produced material, abstract interpretations of objects from the museum’s collection, which – for a brief period – stood in for the real versions in the museum’s display. Some of these objects were absorbed into the collection, but in The Landis Museum there were four objects rejected by the Dahlem. As in the case of Mark Landis, we are not party to the discussions and negotiations that determined the objects’ status; we can only imagine.

Elsewhere, in her video, The Secretary’s Suite, Kiwanga undertook a close analysis of a photograph of the office of Dag Hammarskjöld, Secretary General of the United Nations from 1953 to 1961, who died in mysterious circumstances not long after the picture was taken. With his impending death as a backdrop, she moved from object to object, developing a narrative around diplomatic gift-giving that appeared as bona-fide research, but in which there remains perhaps a hint of conspiracy theory.

Nina Liebenberg

Box with the Sound of Its Own Making (after Morris), 2018

Coloured pencil on paper and audio, 33mins

Nina Liebenberg also undertook a form of object analysis at an institutional border. She spent an afternoon in the strongroom of the University of Cape Town’s special collections department, examining an early 20th century medicine box commissioned for a hunting trip in (then) Northern Rhodesia. Such boxes had been essential parts of the British colonial project, and allowed emigres, missionaries and explorers to venture deeper into unknown territory without fear of contracting tropical diseases. Liebenberg’s verbal report from the strongroom acted as a set of instructions that enabled me to make a drawing of the box, which I had no physical access to, nor visual image of. The instructions Liebenberg sent could be listened to on a set of headphones whilst visitors looked at the drawing.

Helena Hamilton, Dorothy Hunter, Phillip McCrilly & Katrina Sheena Smyth

One-Day Residencies, 2018

Various media

The Derry/Londonderry iteration of The Landis Museum contained an addition ‘local annex’, in which a series of one-day residencies took place over the period of the exhibition. The residencies were choreographed encounters between the existing works and four Northern Irish artists, who were invited to use the gallery as their studio, and to stage a ‘public moment’ at the residency’s conclusion. The artists who took up temporary residency in the annex were Helena Hamilton, Dorothy Hunter, Phillip McCrilly and Katrina Sheena Smyth.

Supported by:

Glasgow International Festival of Visual Art

Culture Ireland

The Arts Council of Northern Ireland